The condition of the Afro-American soldiers within the U.S. Army has always been subject to studies, and their effort to join the fight is now well-known. There are some famous units such as 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion (which was never deployed) or the “Red Tails” (332nd Fighter Group) in the USAAF, and on a larger scale, the 92nd Infantry Division in Italy. However, these frontline units were kind of exceptional, since the U.S. Army wasn’t really keen to deploy “Negro” troops on the frontline. The vast majority of Afro-Americans were assigned to combat service support units, or support units (supply units mainly and sometimes some tank and artillery battalions). At the end of the year 1944, the decision is taken to use “Negro Volunteers” as reinforcements, seeing the high amount of losses within the infantry units.

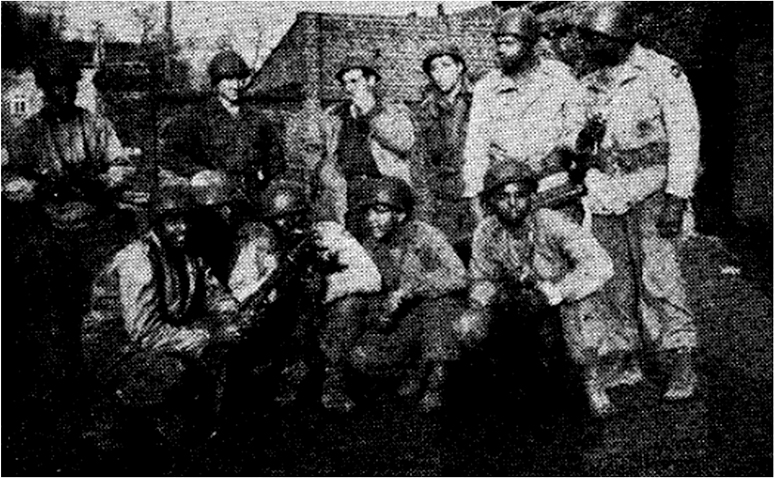

Black Volunteer infantry soldiers prepare for a day’s training in preparation for shipment to veteran units at front lines in Germany

As from this point, the “Negro Volunteers” got organized into reinforcement battalions in which they trained and got ready to be sent towards infantry divisions. They were organized by rifle platoons, and some went to veteran regiments which, like those of the 1st and 9th Divisions, had fought in Europe and Africa. Others went to newer units like the 12th and 14th Armored Divisions, and the 69th, 78th, 99th, and 104th Infantry Divisions. These divisions played varying roles in the concluding months of the war. Some still met hard fighting in their marches across the Rhine and across central Germany; others found resistance collapsing all around them and spent the last weeks of the war rounding up the enemy and establishing provisional military governments.

At the close of the first calendar month after the platoons joined their units, divisions had already formed their impressions of the Negro replacements. The 104th Division, whose platoons had joined while the division was defending the west banks of the Rhine at Cologne, commented: « Their combat record has been outstanding. They have without exception proven themselves to be good soldiers. Some are being recommended for the Bronze Star Medal. » When General Davis stopped at 12th Army Group headquarters on his way to observe the platoons a month after they had joined their units, he found that General Bradley was well satisfied with the reports of the performance and conduct of the Negro reinforcements. General Hodges stated that First Army’s divisions had given excellent reports on their Negro platoons. As General Davis went down through corps and division to regiment and battalion and finally to a company – Company E, 60th Infantry Regiment – he found similar reports of satisfaction. At Company E, the company and platoon commanders and several enlisted men, including the white platoon sergeant, recounted their experiences with enthusiasm. All officers and men, from the regimental commander down, reported high morale and confirmed that the platoon was functioning as planned.

This picture shows a squad of the famous « Fifth Platoon », taken in April in Bitterfeld, Germany.

The 60th Infantry’s Negro platoon – nicknamed the fifth platoon – had had its first heavy going less than a fortnight before, on 5 April, when it and the other platoons of its company took Lengenbach. « This was the colored troops’ first taste of combat, » the regiment’s combat historian recorded, « and they took a big bite. » Four days later one of these men, Pfc. Jack Thomas, won the Distinguished Service Cross for leading his squad on a mission to knock out an enemy tank that was providing heavy caliber support for a hostile roadblock.

Jack Thomas is a recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC), earned during WW II while serving with the 60th Inf Rgt in Europe. When he was recommended for the award by division officers, the request was originally denied until General George Patton approved it personally. Gen Patton knew a brave soldier when he saw one! Thomas is an important figure in the Afro-American military history; during the war, no black soldier was awarded a Medal of Honor, and only nine were awarded the next highest Army award, the DSC. Thomas was one of them. It was not until the late 1990’s that seven African American soldiers were finally awarded the Medal of Honor (MOH). Thomas was one of ten men recommended for the MOH, but was inexplicably dropped from consideration.

Jack Thomas was an orphan from Albany, Georgia. He entered the Army in March 1943 and arrived the European Theater by the end of the year as a truck driver assigned to a service unit. Answering the call in December 1944 for volunteer infantry replacements, Pfc. Thomas was one of the approximately 40 African-American soldiers in the separate platoon assigned to Company E – 60th Infantry Regiment.

During April 1945, the 60th Infantry was engaged in operations to reduce the pockets of German resistance in the Ruhr Valley and the Harz Mountains in western Germany. On 9 April, Company E’s black platoon, reinforced by a bazooka team for antitank defense, was directed to investigate a German roadblock defended by a tank near the town of Herzgerode. Pfc Thomas’ squad and the bazooka team, with Thomas out ahead in the lead, approached to the right of the enemy position to knock out the tank. Deploying into a skirmish line, Thomas and the other men opened fire on the tank o keep enemy soldiers from manning it. Thomas advanced beyond the skirmish line and threw two hand grenades, which wounded several of the enemy. When heavy German fire from automatic weapons and small arms wounded the two bazooka team members, Private First Class Jack Thomas, while under fire, ran to the bazooka position and fired the weapon twice, keeping the Germans away from the tank. As enemy fire continued, Thomas then picked up one of the bazooka men and carried him to safety across a 100 meters clearing.

Company E Commander recommended Private First Class Thomas for a Distinguished Service Cross in early July 1945. The 60th Infantry’s 2nd Battalion Commander quickly approved, as did Colonel William Westmoreland (Regimental CO at that time). By late August, the recommendation medal had reached General Patton, and was approved. After the War, Thomas stayed in the Army and took part to the Korean War. He passed away on 12 November 1987.

Abstract of the Regimental journal « Go Devils » dated from 25 August 1945

Despite the fact that the Afro-American soldiers proved their valor into combat in numerous units on several theaters of operations, they were still not treated well after the war. Veterans reunion organized by the veteran associations often forgot to invite these brave men, for segregation reasons. I hope this article will give them back the place these heroes deserve, among their fellow bothers in arms.

Comments are closed